The Engchoon Kuala Lumpur History Gallery

Source: Provided by CENTRE FOR MALAYSIA CHINESE STUDIES

(1901–1985)

Lin Lian Yu

(Lim Lian Geok)

Lin Lian Yu was born in 1901 in Engchoon, Fujian, originally named Lin Cai Ju. At the age of seven, he began studying classic Chinese with his grandfather and father. When he was sixteen, he went to Xiamen to be an apprentice at a Chinese trad((itional medicine shop, where he spent three years learning the trade. Ultimately, however, he chose a career in education. At that time, Tan Kah Kee was expanding the teacher training department at Jimei School. Lin applied and ranked sixth out of over 140 candidates. During his time at the teacher training department, he was diligent and achieved outstanding academic results, earning the respect of his peers and teachers. He became the first student in the history of Jimei Teachers College to graduate with grades above 90 in every subject, known as a “90 student.”

In 1924, after graduating from the History and Geography Department of Jimei Teachers College, he stayed on as a Chinese language teacher. However, within two years, the school closed due to war and destruction by military party representatives. Lin then moved to Malaya. He first went to Singapore to meet Tan Kah Kee and persuaded him to reopen Jimei School. Subsequently, he went to teach at Ayer Tawar Chinese School in Perak. After a month, he moved to Surabaya to teach. His frequent articles in newspapers aroused suspicion from the Dutch government, leading to unfavorable rumors. He took this opportunity to leave Indonesia.

In 1931, Lin started teaching at Gonghe School in Klang, and six months later, he became the academic director at Yuk Hua School in Kajang. In 1935, he moved to Confucian High School in Kuala Lumpur, where he later became the chairman of the school board after World War II. Witnessing the difficult living conditions of Chinese school teachers, he resolved to unite them. In 1946, he established the Kuala Lumpur Chinese School Teachers’ Welfare Fund and in 1949, organized the Kuala Lumpur Chinese School Teachers’ Association. Lin served as the association’s secretary and from 1951, he was re-elected as its chairman for ten consecutive years.

His main contributions were twofold:

- Internally:

- He fundraised to build a clubhouse, ensuring a solid financial foundation for the association.

- He implemented a welfare system to prevent the families of retired or deceased members from falling into financial despair.

- Externally:

- He fought for pension funds and allowances for Chinese school teachers, enabling them to focus on teaching and improve the quality of education.

- He promoted the respect for teachers, raising their social status.

- He initiated and hosted the All-Malayan Chinese School Teachers’ Conference to oppose the Barnes Report, leading to the establishment of the Malayan Chinese School Teachers’ Association (Jiao Zong).

Lin Lian Yu’s contributions to Chinese education can be summarized into four key points.

First, on December 25, 1951, he established the Federation of Malayan Chinese School Teachers’ Associations (Jiao Zong), to unite teachers, fight for better treatment, and resist unreasonable educational policies.

Second, he consistently defended Chinese education with unwavering dedication. During a time when many policies were detrimental to Chinese education, he rallied the Chinese community to oppose them collectively.

Third, he advocated for the Chinese community to obtain citizenship, recognizing the shift in national consciousness among Malayan Chinese. In the 1950s, although local Chinese recognized this country as their home, they faced numerous obstacles in obtaining citizenship. Lin Lian Yu led Jiao Zong and other Chinese organizations in holding the All-Malayan Chinese Associations’ Citizenship Convention in Kuala Lumpur. The enthusiastic response led to over 700,000 Chinese gaining citizenship before independence.

Fourth, he worked to eliminate the confrontation between Dong Zong (United Chinese School Committees’ Association) and Jiao Zong, transforming the two major organizations into the vanguards of Chinese education. They joined forces in their struggle for Chinese education, a partnership that continues until today.

In 1954, when Lin Lian Yu became the chairman of Jiao Zong, his first challenge was the 1954 Education White Paper. This document stipulated that all Chinese primary schools within the Federation must open English classes to “bring the spirit of national education into vernacular schools.” Lin Lian Yu recognized this as a strategy to erode Chinese schools and decided to oppose it vehemently. At the end of 1954, as Jiao Zong’s chairman, he issued a letter to local teachers’ associations, all Chinese school teachers, and parents, stating their support for the Chinese-Malay alliance in the elections and revealing Jiao Zong’s three main goals for the first time: (1) equal education for all ethnic groups; (2) the development of mother tongue education; and (3) the recognition of Chinese as an official language.

To fight for the interests of Chinese education, on January 12, 1955, Lin Lian Yu led a delegation from Dong Zong and Jiao Zong to meet with Tunku Abdul Rahman at Tan Cheng Lock’s residence in Malacca. Although the tangible results of the meeting were not significant, there were two unexpected outcomes: (1) it established Dong Zong and Jiao Zong’s position as representatives of Chinese education; (2) it prompted Sir Tan Cheng Lock to advocate more vigorously for the rights of Chinese education in the future.

In 1954, the two major leaders of Malaysian Chinese education met when Lin Lian Yu welcomed Tan Lark Sye, the chairman of the Nanyang University Executive Committee, to Kuala Lumpur. Both individuals had their citizenships revoked by their respective governments due to their efforts in defending the rights of Chinese education

Source: Provided by Centre for Malaysian Chinese Studies

In 1952, during the opening ceremony of the new clubhouse of the Kuala Lumpur Teachers’ Association, Chairman Lin Lian Yu gave a speech. Seated beside him was the invited guest, Deputy Director of Education for the Federation, Payne, who officiated the ribbon-cutting

Source: Provided by Centre for Malaysian Chinese Studies

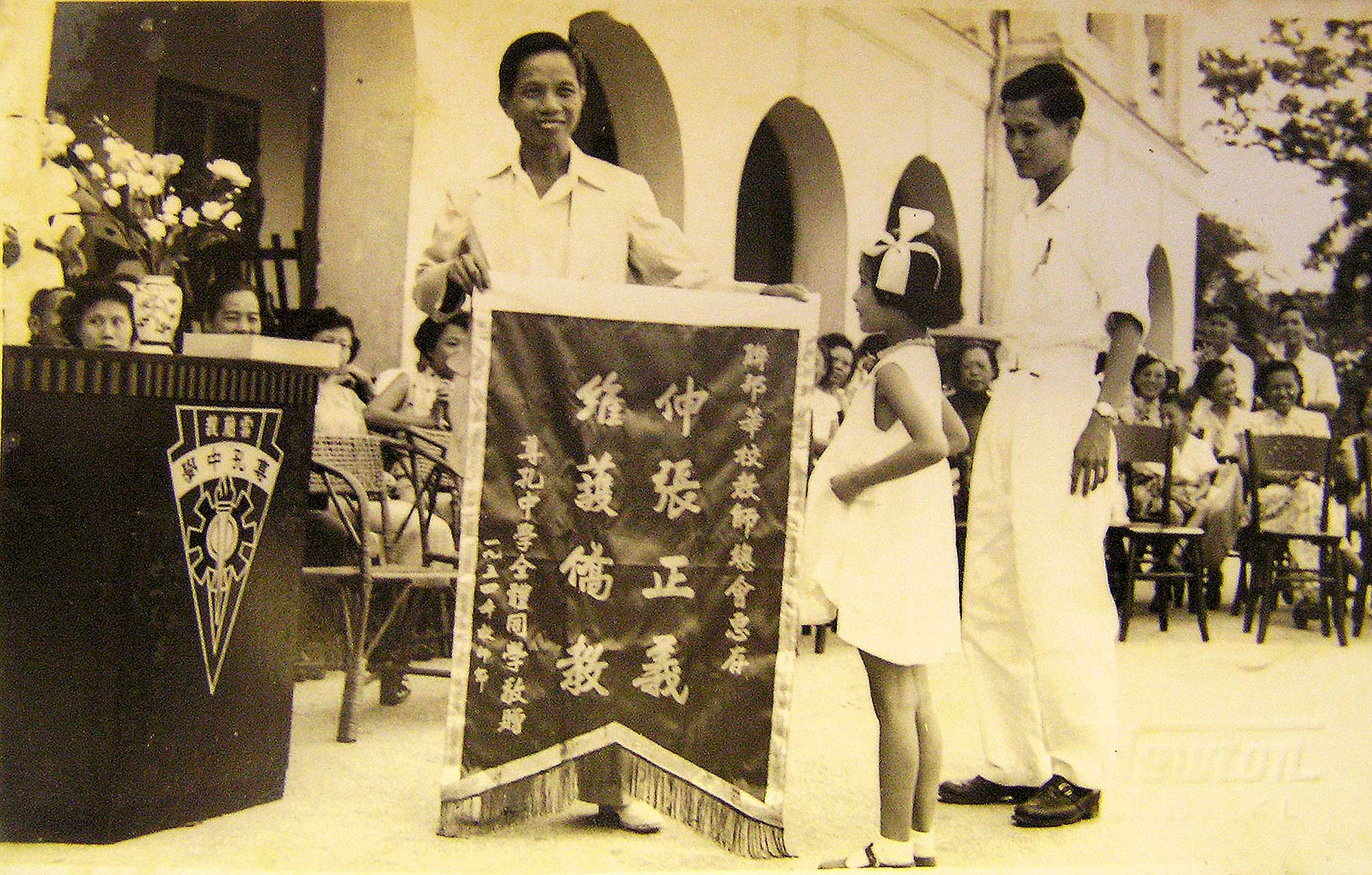

In 1954, during the Confucian School’s celebration of Teachers’ Day, all the students presented a silk banner to Jiao Zong in recognition of its efforts in safeguarding Chinese education. The banner was received by Lin Lian Yu, who was the deputy principal of Confucian School and the chairman of Jiao Zong at the time

Source: Provided by Centre for Malaysian Chinese Studies

Lin Lian Yu served as the chairman of the Federation of Malayan Chinese School Teachers’ Associations (Jiao Zong) for eight years. In 1956, the Malayan government drafted the Razak Report, which excluded Chinese secondary schools and proposed that the ultimate goal of education in the country was to use the national language (Malay) as the medium of instruction in all schools. As Jiao Zong’s chairman, he led opposition efforts and negotiated with the then Minister of Education, Abdul Razak. Ultimately, he succeeded in ensuring that the “ultimate goal” was not included in the 1957 Education Act.

A few years later, in 1961, the Malayan government introduced the Rahman Talib Report, which required Chinese secondary schools to convert into English-medium schools or lose their subsidies. At that time, Chinese education was facing a critical threat. Lin Lian Yu warned, “accepting the conversion leads to a dead end. Chinese secondary schools are the bastions of Chinese culture. Subsidies can be withdrawn, but independent Chinese schools must continue.” His firm stance led to a fierce debate with Leong Yew Koh, a prominent leader of the Malaysian Chinese Association and one of the review committee members of the education policy. Due to his leadership in opposing the 1961 Education Act, the Malayan government accused him of deliberately distorting and reversing government educational policies and inciting racial sentiments. Consequently, the Ministry of Education revoked his teaching license, and the Ministry of Home Affairs stripped him of his citizenship.

Lin Lian Yu was also a writer, publishing articles under the pen name Kang Ru Ye. His published works include “Fragments of Memories,” “Appeals for Chinese Education,” “Collected Essays of Wu Gou,” “Assorted Writings,” “Eighteen Years of Storms” (Volumes 1 and 2), and “Collected Writings of Jiang Gui.” He also published “Collected Poems of Lian Yu,” which compiled poems reflecting his thoughts on current events.

He passed away on December 18, 1985, due to illness. In recognition of his contributions to the nation and the Chinese community, fifteen Chinese organizations, including Jiao Zong, Dong Zong, and the Selangor Chinese Assembly Hall, established the “Lin Lian Yu Foundation” and designated the anniversary of his death as Malaysian Chinese Education Day starting in 1987. Although he was stripped of his citizenship and teaching license in 1961, and faced financial difficulties in his final 24 years, he remained deeply concerned about the development of Chinese education in Malaysia. If someone sought his opinion on Chinese education, he was always willing to share his thoughts. In September 1985, just months before his death, he expressed his concern and support when he heard that Dong Zong and Jiao Zong were planning a dialogue with the Islamic Party of Malaysia (PAS). During his illness, even when he was bedridden, he frequently inquired about the publication status of “Jiao Zong’s 33-Year History.” In his last 24 years, there were obviously fewer speeches, but most of his quoted words come from this period.

Lin Lian Yu passed away suddenly. Fifteen Chinese organizations formed a funeral committee to manage his funeral and posthumous affairs. To facilitate public mourning, the Selangor Chinese Assembly Hall broke a 60-year tradition by converting its main hall into a memorial hall to honor him. Over three days, tens of thousands paid their respects. On the day of the funeral, the procession stretched for a mile, with tens of thousands of mourners lining the streets in solemn tribute. Subsequently, memorial services were held across various regions, marking a rare and highly respectful farewell.

Note: This article is excerpted from “Biographies of Malaysian Chinese” Volume 2, pages 818-821, written by Xie Chuan Cheng.