The Engchoon Kuala Lumpur History Gallery

Lim Lian Geok’s

Defending Chinese Education Movement

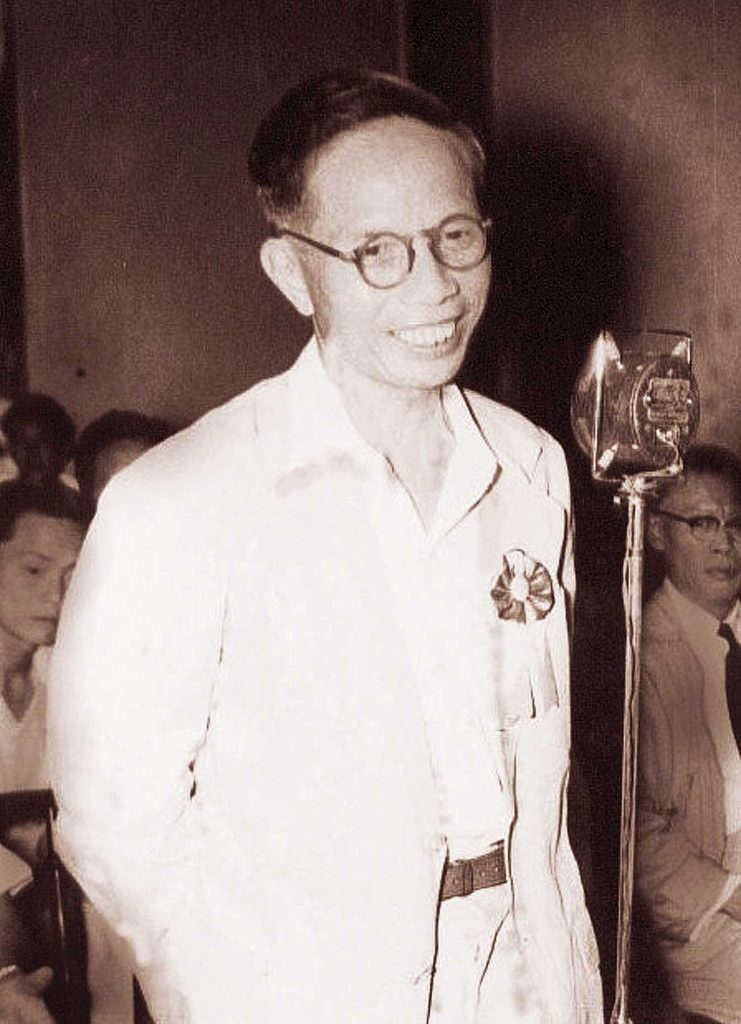

After experiencing the unfair policies enacted by the British colonial government and the Malayan government, the Chinese community began to develop a sense of crisis. Concerning the interests of Chinese society as a whole, especially on issues of defending the rights of Chinese education, various dialect groups became self-aware and engaged in resistance movements, transcending the boundaries of clans to seek solutions from the perspective of the “Chinese” as a whole. Among these efforts, the most notable was Lim Lian Geok’s fight to have Chinese as an official language and his leadership in opposing policies detrimental to the development of Chinese education. Consequently, Lim Lian Geok became a significant figure in the historical progression of the Chinese community in post-independence of Malaya (Malaysia).

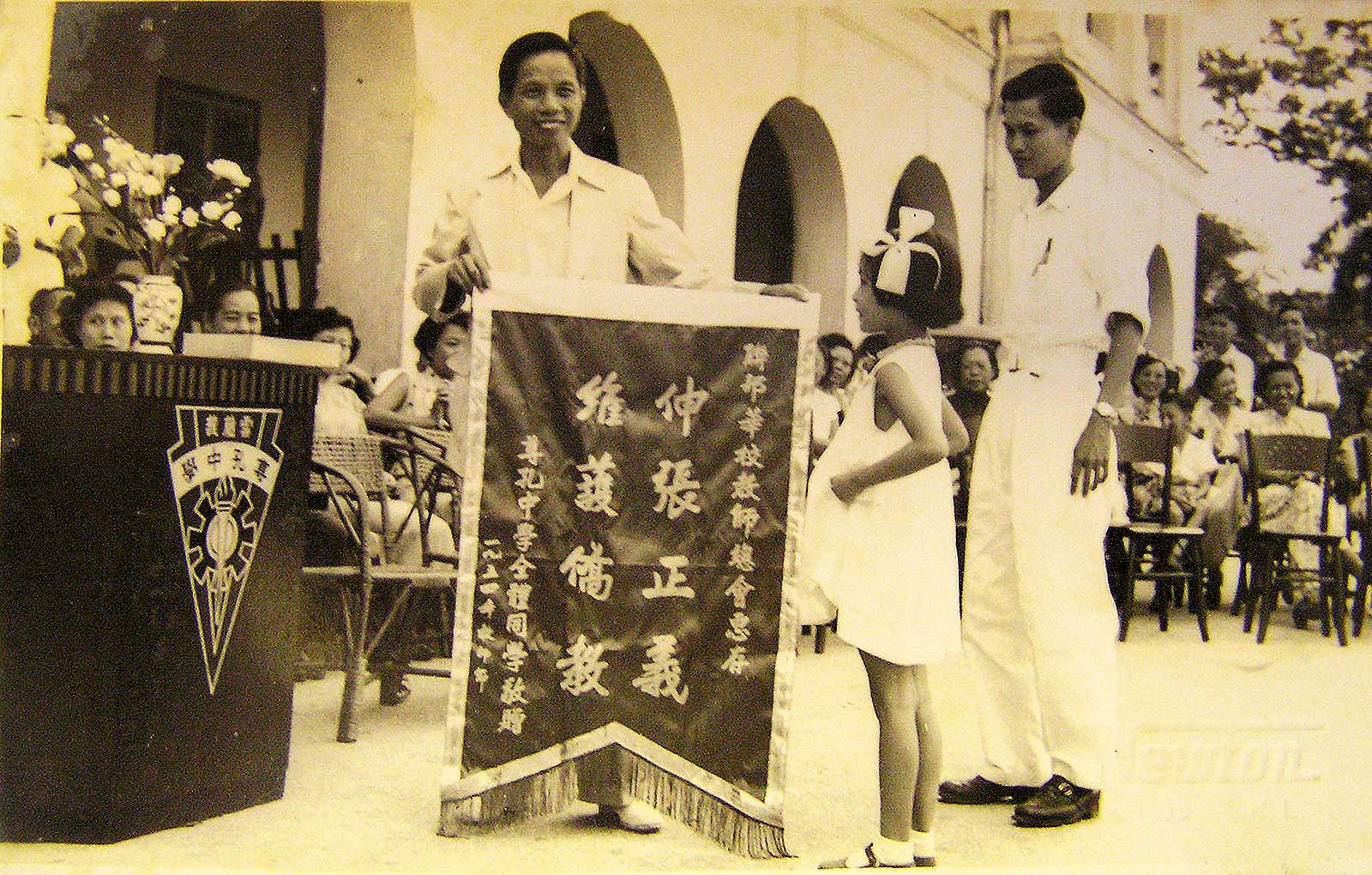

Born in 1901 in Engchoon, Penghu, Lim Lian Geok graduated from Jimei Normal School in Xiamen, Fujian Province, before coming to British Malaya to pursue a teaching career. While holding a teaching position in Kuala Lumpur, he tirelessly visited every Chinese school in the city to improve teachers’ welfare and advocated for the organization of a teachers’ union. This effort led to the establishment of the Kuala Lumpur Chinese School Teachers’ Union in 1949, and he became the president in the following year. During the same period, Lim Lian Geok was also active in the Engchoon Association, serving as the secretary of the Kuala Lumpur Engchoon Association from 1951 to 1961. Furthermore, he was the founding secretary of the National Engchoon Association of Malaya from 1957 to 1962. These roles reflect his multiple identities as a native, a professional, and a Malayan citizen.

After organizing the Kuala Lumpur Teachers’ Union, Lim Lian Geok boldly criticized the policies enacted by the British colonial government that were detrimental to the development of Chinese education. When the government released the Barnes Report, Lim Lian Geok was the first to oppose it and successfully unified teachers’ unions nationwide, leading to the establishment of the Malayan Teachers’ Union (known as “Jiao Zong”). He assumed the position of president in 1954. Besides being vocal on educational issues, Lim Lian Geok also made recommendations regarding citizenship and the inclusion of Chinese as an official language.

In September 1951, Lim Lian Geok formally applied for Malayan citizenship. In April 1956, he facilitated the National Chinese Associations’ Conference for Citizenship, where he served as the drafter of the conference declaration. The conference put forward four major demands: the automatic citizenship for those born locally; the right to apply for citizenship after five years of residence; the equal obligations and rights for all citizens; and the Chinese as one of the official languages. Even before independence, Lim Lian Geok demonstrated a commitment to national identity in Malaya. His role in drafting the citizenship conference declaration reveals his awareness of the threat that Chinese people might become second-class citizens after Malayan independence.

In 1960, following the release of the Rahman Talib Report and the subsequent 1961 Education Act, Lim Lian Geok criticized these measures, believing they were detrimental to the development of Chinese education in Malaya. Due to his established reputation in the Chinese community as someone who dared to speak out, his criticisms quickly sparked a massive wave of opposition among the public, putting significant pressure on the government. This, in turn, angered the ruling authorities, especially the chauvinists within UMNO, who advocated for harsh actions against Lim Lian Geok. Thus, the authorities employed the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) to attack him and abused their power to treat him unfairly. On August 12, 1961, Mr. Lim Lian Geok received a notification signed by the Director of the National Registration Department under the Ministry of Home Affairs. The letter informed him that due to his deliberate distortion and misrepresentation of government education policies, as well as his motives of an extremely racial nature, which incited animosity and hostility among different ethnic groups and could potentially cause unrest, his citizenship would be revoked. Subsequently, on August 21, his teaching license was also revoked.

In 1954, two major figures in Malaysian Chinese education met when Lim Lian Geok welcomed Tan Lark Sye, the chairman of the Nanyang University Executive Committee, to Kuala Lumpur. Both individuals had their citizenship revoked by their respective governments due to their efforts in defending the rights of Chinese education

Source: Provided by Centre for Malaysian Chinese Studies

Lim Lian Geok’s plight garnered sympathy from the Chinese community, and his sacrifices for the cause of Chinese education cemented his esteemed position in history of Chinese education. Placing personal gains and losses aside, he took it upon himself to defend the civil rights of the Chinese, setting the tone for the development of Chinese education in Malaya and having a profound influence on future Chinese educational movements. Although Lim Lian Geok took the revocation of his citizenship by the government to court, ultimately to no avail, he marked the first step towards a civil society within the history of Chinese associations. His efforts, though unsuccessful, awakened the Chinese community’s awareness of the need to defend their rights.

Post-independence, a series of controversial measures taken by the Malayan (Malaysian) government, such as the transformation of Chinese independent high schools, the rejection of Merdeka University’s application, and appointing non-Chinese-speaking individuals as deputy principals in Chinese primary schools, sparked intense backlash from the Chinese community. Movements such as the revival of Chinese independent schools, the establishment of the Civil Rights Committee, and the Chinese associations’ demands during the 1999 general election demonstrate the community’s unwavering stance against the targeted measures by the authorities.

Following Lim Lian Geok, most of the presidents of the Malayan Teachers’ Union were pioneers in defending Chinese education, with Mr. Sim Mow Yu being a prominent example. He adhered to Lim Lian Geok’s path of struggle and was expelled from the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) for advocating the inclusion of Chinese as an official language. Since its inception, the stance of the Malayan Teachers’ Union has been to defend the sound development of mother tongue education. The Malayan Teachers’ Union, together with the United Chinese School Committees’ Association of Malaysia (UCSCAM), is known as Dong Jiao Zong, being the highest authority in Chinese education. The unyielding efforts of Dong Jiao Zong have been crucial in maintaining the integrity of Chinese education from primary to tertiary levels since independence. Lim Lian Geok’s fearless and uncompromising spirit is the most important legacy of Dong Jiao Zong. Overall, Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao’s reformist faction and Sun Yat-sen’s Tongmenghui laid the foundation for the birth of modern education in the early 20th century. Half a century later, Lim Lian Geok established the struggle route for defending mother tongue education in Malaya. The Malayan Teachers’ Union and UCSCAM have inherited Lim Lian Geok’s fighting spirit, curbing the risk of external interference degrading Chinese education.

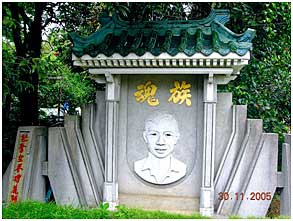

Lim Lian Geok passed away in Kuala Lumpur in 1985. His tombstone bears the inscription of “Soul of the Race”, a tribute from the Chinese community recognizing his contributions to defending their rights. Led by the Malaysian Teachers’ Union, the fifteen Chinese associations established the “Lim Lian Geok Foundation”, which holds an annual memorial service on December 18th, known as Chinese Education Day. These measures not only commemorate Lim Lian Geok’s contributions to Chinese education in Malaysia but also remind future generations of the fundamental principles that must be upheld in Chinese education. The foundation created the “Lim Lian Geok Spirit Award” to honor individuals who have made outstanding contributions to Chinese education in Malaysia, reinforcing the historical memory of Chinese education.

Lim Lian Geok’s experiences also warrant reflection. Chinese education, constrained by Malay chauvinism, became entangled in political struggles and used as a tool by both ruling and opposition parties. Lim Lian Geok’s fate is a result of the politicization of educational issues. In the early years of independence, Malays lacked confidence and feared the political rise of the economically advantaged Chinese. As a result, UMNO’s political elites suppressed Chinese rights and prevented them from fair sharing of national resources. Meanwhile, opposition Chinese left-wing parties often exploited Chinese education issues for political gains. Despite facing dirty political tactics and knowing that defending Chinese rights posed significant risks, Lim Lian Geok, a native of Engchoon, courageously fought for the basic citizen rights of the Chinese, becoming a benchmark figure in the Chinese community.

Lim Lian Geok’s cemetery has become the site for the annual memorial service during Chinese Education Day

Source: Provided by Lim Lian Geok Foundation