The Engchoon Kuala Lumpur History Gallery

The Development and Chinese Pioneering of

Kuala Lumpur

Before the development of Kuala Lumpur, several places in Selangor were already engaged in tin mining activities. The development of the entire state of Selangor was closely linked to the tin mining industry, particularly the construction and growth of Kuala Lumpur, which was founded on the local tin mining industry.

The Development of

the Selangor Mining Industry and

the Formation of Inland Settlements

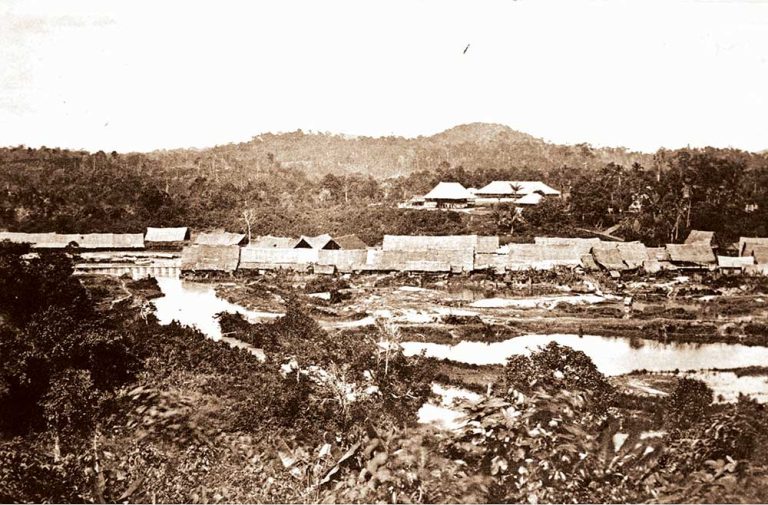

The Development of the Selangor Mining Industry and the Formation of Inland SettlementsThe formation of settlements in Selangor during the nineteenth century can be broadly categorized into two types. One type consists of settlements that naturally formed along the coast and riverbanks. The other type includes inland settlements that developed due to tin mining activities. The earliest mining areas were Lukut (which originally belonged to Selangor and was only ceded to Negeri Sembilan in 1878), Kanching, and Ampang to Kuala Lumpur. Some towns in central and eastern Selangor were developed alongside the rise of tin mining activities.

By the mid-nineteenth century, many settlements had emerged within Selangor, primarily due to the development of the tin mining and agricultural industries. The population of these settlements mainly migrated from river mouths or coastal areas.

Source: Provided by Centre for Malaysian Chinese Studies

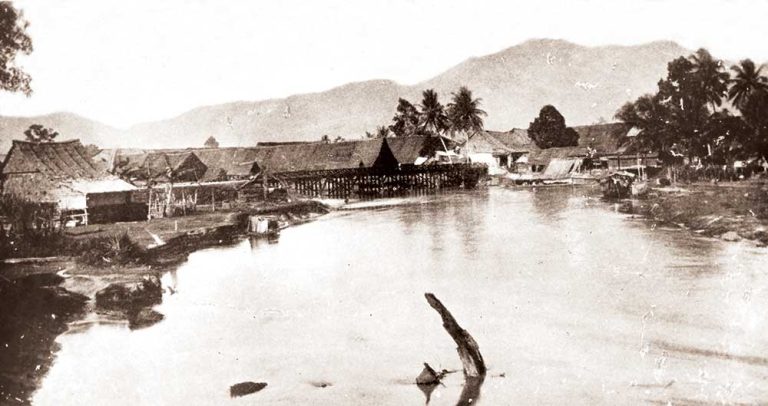

In 1857, Raja Abdullah, the son-in-law of Sultan Muhammad, borrowed 30,000 dollars from Malacca Chinese merchants Hsu Yenchuan and Lim Say Hoe to bring 87 Chinese miners from Lukut to the Ampang area of the Klang River basin (present-day Ampang) to mine tin. However, many of the miners died from illness, leading to the failure of this initial venture. Later, Raja Abdullah recruited another 150 miners from Lukut to continue searching for tin, and after two years, they finally found tin deposits. This marked the beginning of the mining settlement in Kuala Lumpur, which quickly attracted more miners and Chinese immigrants. In 1880, after the British colonial government moved the capital of Selangor from Klang to Kuala Lumpur, the city rapidly developed into the commercial center of Selangor.

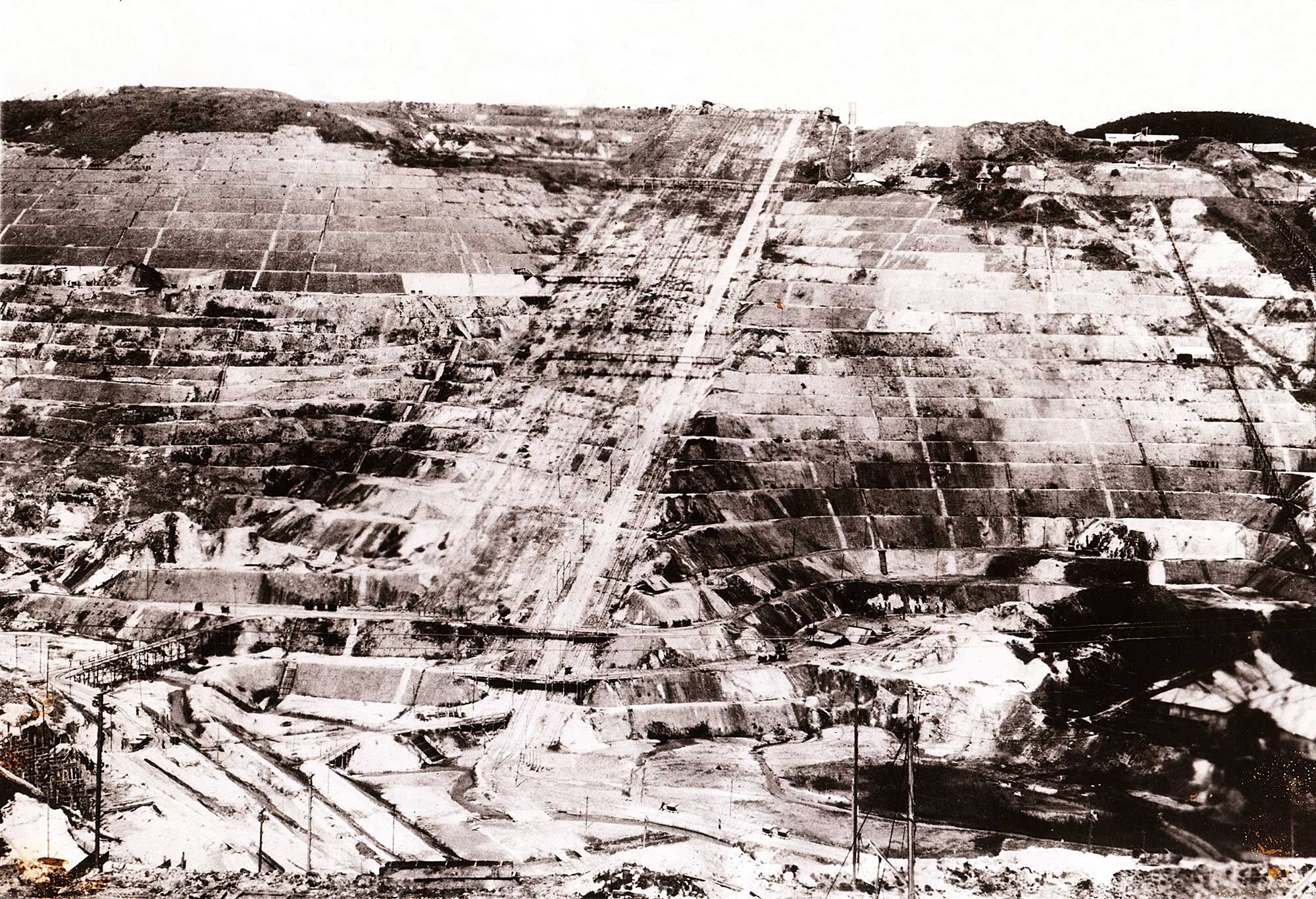

The tin mining industry was the economic foundation for the formation of settlements around Kuala Lumpur. The image shows a major mining site in Serdang in 1941

Source: Provided by Centre for Malaysian Chinese Studies

The Economic Development Trajectory

of Selangor Before World War II

By the late 19th century, rice, pepper, sago, coffee, gambier, and cassava had become important products of the Selangor plains. The Chinese began engaging in plantation agriculture in 1870 when Yap Ah Loy established a gambier plantation in Kuala Lumpur. He also planted gambier near Sungai Way in Petaling. In 1884, the British colonial government enacted specific regulations to encourage the cultivation of gambier and pepper in Negeri Sembilan, Perak, and Selangor. Consequently, gambier and pepper plantations of various sizes emerged in Kuala Langat, Kuala Lumpur, and Ulu Langat. In 1903, as the prices of gambier and pepper fell while rubber prices surged, gambier and pepper gradually disappeared. Coffee prices also dropped, and pest infestations led many plantation owners to switch to rubber cultivation.

Tin mining only gradually became the economic lifeline of Selangor in the mid-19th century, with most tin mining areas concentrated in the eastern half. Towns such as Kuala Lumpur, Ampang, Sungei Buloh, Kajang, Simpang Lima, Beranang, and Serdang were developed due to mining activities. The growth of the tin mining industry also stimulated the demand for food cultivation and commercial activities, causing small settlements to gradually expand into towns and cities.

Lukut was the earliest developed mining area in Selangor, predominantly populated by Hakka miners. Subsequent mining areas in Kanching and Kuala Lumpur were also developed by the Hakka community. These regional ties significantly contributed to the economic expansion of Selangor. Another reason for the concentration of Hakka people in Selangor was that the major tin mining areas in Perak, the largest tin-producing state in Malaya, had already been occupied by Cantonese and Teochew people. Consequently, the Hakka had to explore later-developing areas like Selangor for mining opportunities, establishing many mining settlements there.

The development of mining areas provided employment opportunities for Chinese immigrants, leading to a population surge in these settlements. By the late 19th century, the Chinese population in Selangor was mainly concentrated in these mining areas. These mining areas were primarily controlled by a few large mining magnates. For example, Yap Ah Loy, the largest tin miner in Selangor, owned over 1,000 acres of mining land in the state by 1882. The development of areas such as Ampang, Petaling, Kepong, Kuala Kubu, Pudu, and Sungei Buloh was directly or indirectly related to his tin mining activities. Other prominent mining magnates of the time included Yap Chit Ying, Yap Kwan Seng, Cheow Yoke, and Loke Yew.

The prosperity of the tin mining industry also spurred agricultural development. Before the rise of the tin mining industry, the demand for agricultural products in Selangor was low. However, as mining areas developed, miners were too occupied with mining activities to grow their own food, necessitating the provision of daily rice supplies by nearby villages. Thus, the agricultural land around the mining areas rapidly expanded with the development of the mines and the increase in the resident population.

Rubber was the most important economic crop during the early stages of Malaya’s independence.

Source: Provided by Centre for Malaysian Chinese Studies

The data from the Membership Register of the Selangor Pahang Rubber Merchants Association shows that the vast majority of rubber merchants who joined the association from 1946 to 1960 were from Engchoon. Before Malaya’s independence, specific community boundaries existed in various industries. Engchoon people held significant positions in the rubber industry. Apart from being predominantly involved in tapping rubber as rubber farmers and workers, another crucial aspect was their involvement in the grocery business, which laid the foundation for the construction of the rubber industry network. Early transactions between rubber farmers in rural areas and grocery stores often involved credit arrangements for rice and provisions, with rubber sheets used as payment. The network of people from the same hometown established specific commercial activity boundaries for grocery and rubber purchasing in rural areas. In Kuala Lumpur, most were wholesalers and secondary traders. The geographical ties of the same hometown further strengthened the business connections.

In the early 20th century, an increasing number of Chinese immigrants engaged in business across various parts of Selangor. With the population growth, the demand for housing also increased, leading to the emergence of timber factories and hardware stores. The economic value of rubber products increased due to growing foreign demand, leading to the establishment of rubber processing factories. Additionally, the food industry experienced rapid development in response to the improved economic conditions and population growth. Before World War II, Selangor was already a region characterized by the coexistence of mining, rubber, commerce, and agriculture.

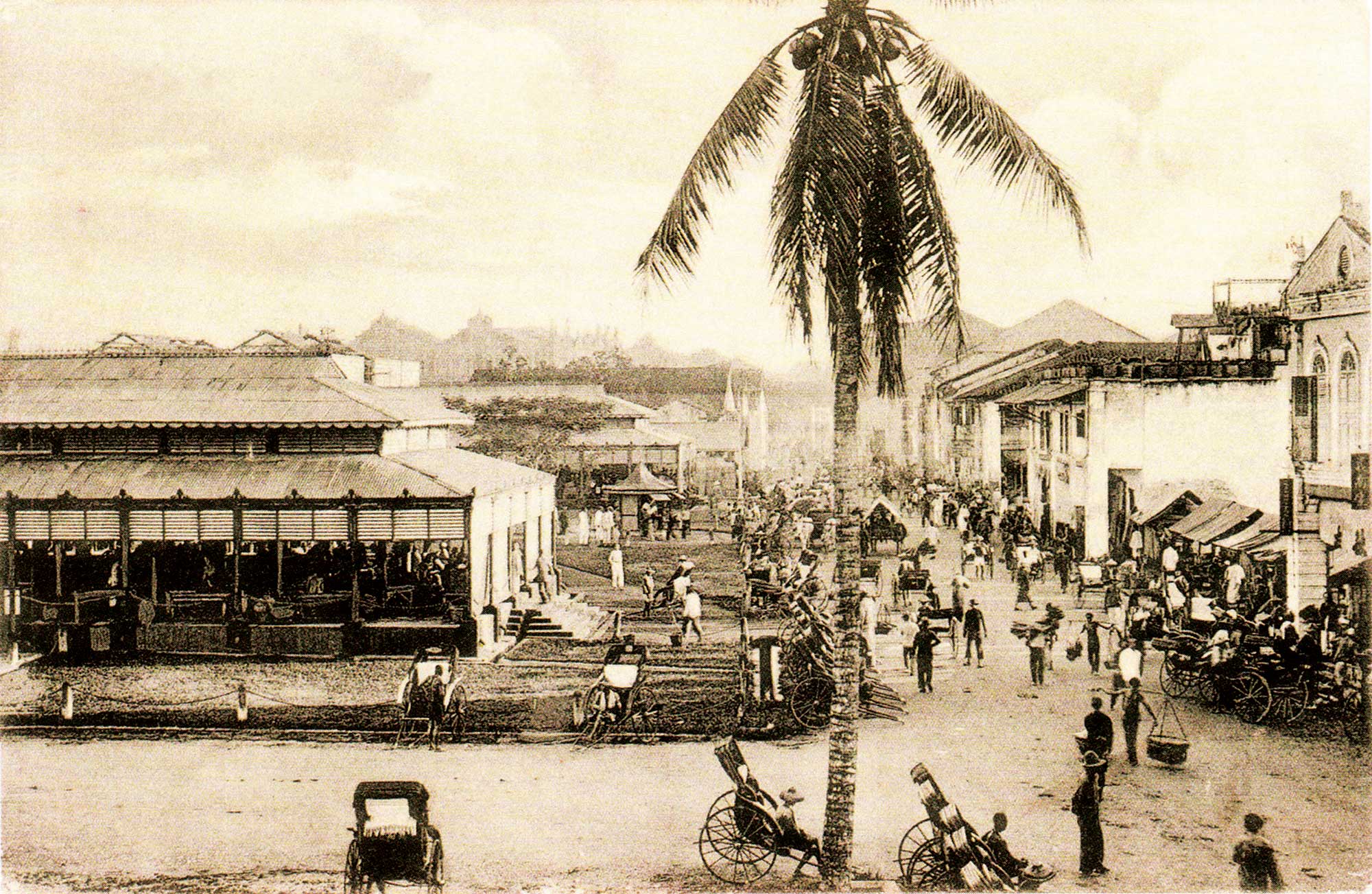

The exterior of the Central Market in Kuala Lumpur in the early 20th century.

Source: Provided by Centre for Malaysian Chinese Studies

Changes in the Structure and Distribution of

the Chinese Community in Selangor

In 1911, among the Chinese community in Selangor, Hakka and Cantonese people were the predominant groups, with Hokkien people ranking third. However, their proportion had surged from 8.6% a decade earlier to 18.41%. The fluctuations in the proportion of various dialect groups were influenced by specific factors at the time.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the tin mining industry in Selangor was largely controlled by several prominent Cantonese mining magnates, such as Chen Xiulian, Chen Zhanmei, and the Loke brothers. Chen Xiulian and Loke Yew were appointed as members of the state council and transferred part of the lease contracts to Cantonese people, attracting more Cantonese to Kuala Lumpur. The origin of employers influenced the formation of community boundaries in the industry. By the early 20th century, Cantonese people had replaced Hakka people as the leading group in the tin mining industry in Selangor.

By the end of the 19th century, inland towns developed in the mining areas were predominantly populated by Hakka and Cantonese people. Coastal towns from Sepang to Tanjong Sepat were the most concentrated areas for Hokkien people, especially in Klang, where they accounted for more than half of the population. The significant increase in the Hokkien population in Selangor from 8.6% to 18.41% within 20 years was primarily due to the rise of the plantation industry.

By the time of World War II, there had been significant changes in the structure of the Chinese community in Selangor. In 1931, the Hokkien population had grown to 67,405, surpassing the Cantonese and becoming the second-largest dialect group. The Hakka population remained the largest, reaching 80,167. However, after World War II, the Hokkien population surged to 113,123, making them the largest dialect group in Selangor.

The number of Hokkien people in Selangor was only 5,367 in 1891 but surged to 32,174 in 1911, and further rose to 67,405 in 1931, and peaked at 113,123 in 1947 after World War II. Selangor developed alongside the tin mining industry, dominated by Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups. After the influx of Hokkien people, they could only engage in small businesses in urban areas or endure hardships in the suburbs, contributing to the development of rubber plantations. This subsequently led to the Hokkien people’s dominance in the rubber and commercial sectors. Coastal towns in Selangor were mostly developed due to plantation activities. Areas with concentrated Hokkien communities, such as Sungai Buloh, Ijok, Batang Berjuntai, Rawang, Serendah, Tanjung Sepat, and Sungai Pelek, developed rapidly in the early 20th century due to the prosperity of the plantation industry.

The Selangor Hokkien Association was established in Kuala Lumpur in 1885. Although the number of Hokkiens in Kuala Lumpur County and Kuala Lumpur City was only over 4,000 in 1891, the establishment of the Selangor Hokkien Association indicated a high level of cohesion among Hokkien people at that time. Engchoon people, who were only the third-largest dialect group within the Hokkien community before World War II, began establishing networks in the rubber industry, particularly during the early 20th century when rubber business flourished, solidifying their social status within the Chinese community in Kuala Lumpur.